When the going gets tough, most parents try to protect their offspring. But the warty comb jelly takes a different tack: it eats them.

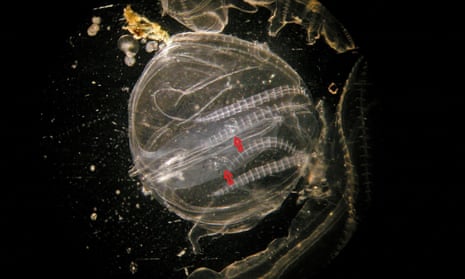

Despite initial appearances, comb jellies are not jellyfish but belong to a different group of animals, ctenophora, which swim using tiny hair-like projections called cilia.

While the warty comb jelly is native to the east coast of America, it has caused chaos in European waters where it eats fish larvae and the prey of fish. Indeed, the species caused a collapse of fisheries in the Black Sea in the late 1980s.

“The Black Sea just became this gelatinous ocean,” said Dr Thomas Larsen, an ecologist at Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

Now Larsen and colleagues say the discovery of cannibalistic tendencies among Mnemiopsis leidyi may help to explain why the creatures appear to thrive in European waters even when prey is scarce, and could shed light on how to tackle the invasive species.

“By knowing the lifecycle and strategies of this species, we can more easily devise more efficient conservation strategies,” Larsen said.

The research team add that with comb jellies cropping up early on the evolutionary tree of animals, the discovery could also have wider implications, raising the question of whether the behaviour has cropped up independently multiple times among multicellular animals, or is a basic trait.

Writing in the journal Communications Biology, the researchers report how they looked at the abundance of the warty comb jelly in the Kiel fjord in Germany on a daily basis from August to October 2008, hoping to unpick a puzzle. Why do they produce huge numbers of offspring in the late summer when larvae are unable to survive the winter?

The team found the population of warty comb jellies reached a peak in early September. “They are very prolific. An adult lays up to 12,000 eggs in two weeks,” said Larsen. But while their overall abundance fell after this point, the ratio of adults to larvae increased – despite the adults’ prey plummeting from early September and the prey of the larvae becoming more abundant.

The researchers say the results suggest an unexpected explanation: adult warty comb jellies eat their young. “If larvae were not taken by adults, they could also contribute to the pool, by producing new larvae,” said Dr Jamileh Javidpour, the lead author of the study, from the University of Southern Denmark, adding that during the work the team discovered comb jelly larvae inside the stomach of an adult.

Further experiments, in which adults and larvae were placed in a tank together, confirmed the grisly phenomenon, while additional analysis revealed that the nutrients obtained through cannibalism – although less than from eating typical prey – could sustain the adult comb jellies for an extra two or three weeks in the sea. That means the late summer bloom not only helps the comb jellies out-compete other creatures but also allows them to build up nutrient reserves to survive the winter ahead.Dr Sophie Pitois, a senior marine scientist at the UK’s Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas) who was not involved in the research, said: “The authors present a new insight into how a non-native and invasive species can survive and become established in environment far away and with very different environmental conditions from its original conditions.

“To the best of my knowledge, these findings are new and provide an opportunity to rethink and design appropriate conservation strategies in controlling the spread of non-native invasive species by taking into account the entire range of an animal behaviours that allow it to adapt and thrive in new environments.”