The Most Sensual Georgia O'Keeffe Flowers in Paintings

For anyone not familiar with Georgia O'Keeffe's art and its readings, a search of the internet with just three keywords - Georgia O’Keeffe flowers – may come with surprising results. The majority of texts on the first several pages of the results will be with similar titles. They put these three words in conjunction with the word vagina, or vulva, as if something that naturally comes together. But how the link between Georgia O’Keeffe flowers and vagina became so strong that is unavoidable today, and more importantly, how much veracity is in it? Can we ascribe her work to this singular interpretation, leaving aside all others, and how did this perspective start to dominate over others, especially if we had in mind that the artist rejected it herself?

These are just some of the legitimate questions the search results may provoke, but the answer to them requires a much deeper exploration of O’Keeffe’s flowers and contextual background that surrounds them. In the 20th century rife with male artistic geniuses and expressive power of splotched masculinity, as in drip paintings of Jackson Pollock, the femininity became the prerogative of the sensual, delicate, and vulva-like flowers. Being another extreme of the reductive readings of gender and sex, O’Keeffe’s flowers served as a battlefield for opposing interpretations in which the artist herself often took an active part. In recent years, however, there are attempts to shift the interpretative framework of Georgia O’Keeffe flowers away from gendered readings, which are considered conservative and outdated.

Georgia O'Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz - From Vagina to Marriage

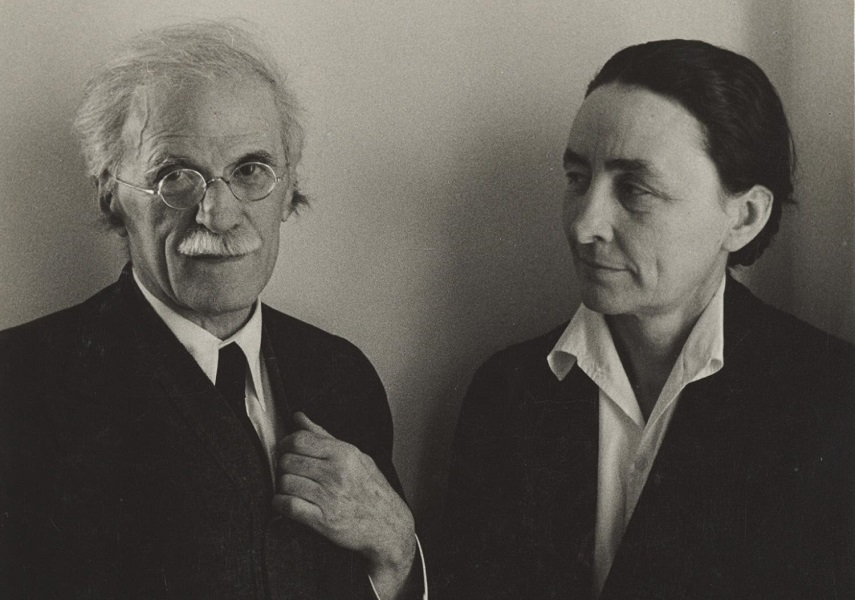

The life of Georgia O’Keeffe is well documented. She was a very passionate and highly intelligent woman, who was primarily interested in beauty, form, and design. After her initial art training at School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Art Students League of New York, she worked as an illustrator as she was unable to continue her studies due to financial difficulties. In autumn 1915 she sent some of her charcoals to a friend in New York, who showed them to a prominent photographer, Alfred Stieglitz. Impressed by her works, Stieglitz held a few exhibitions of her work in his 291 Gallery, and the pair married in 1924.

The theory mentioned above, which links Georgia O’Keeffe flower paintings with the metaphorical representations of female genitalia, was first proposed by Stieglitz, in 1919, before they got married. At the time Stieglitz was a member of a circle of New York creatives who used themes of sexuality in their works as a mean through which they declared their belonging to the avant-garde. This included the reading of Sigmund Freud’s books, among other popular literature on sex and psychology. Havelock Ellis’s Studies in the Psychology of Sex, which argued that all art is fueled and driven by sexual energy, seemed to influence Stieglitz the most, when he suggested that O’Keeffe’s flowers are metaphorical studies of vulva. Although the artist later vehemently rejected this reading, the interpretation stuck to this day, raising further debates on who is allowed to produce knowledge, and whose opinions matter the most.

O’Keeffe and Feminism - A Troubled Relationship

The subject matter of a painting should never obscure its form and color, which are its real thematic contents.

This statement by O’Keeffe should have put to rest all the debates about whether her flowers represent female genitalia, but it was not quite so. Later women artists even championed this vaginal reading of her works. Feminists in the 1970s particularly embraced this interpretation as they saw her works as empowering to women, and as a clear statement of female agency in the art world. For them, Georgia O’Keeffe flowers were metaphorical representations of female body, created in contrast to the traditions of female nudes painted by male artists, and from male audiences.

Judy Chicago celebrated O’Keeffe in her work The Diner Party, where she gave her a place setting with the vaginal ceramic ‘portrait’. However, this appropriation of her art by feminists enraged O’Keeffe, who insisted that she is not a feminist, and that she is not a woman painter, but just a painter. Regardless of her protests, her art offered to women artists a model of self-empowerment and female independence that inspired many of them.

What Georgia O’Keeffe Said – Flowers as Her Flowers

O’Keeffe started exploring the motif of flowers early in her career. She was initially attracted to flowers due to their intricate forms and colors, which often posed a challenge to observation, and especially representation. She experimented with forms and approaches before settling on a close-up approach in depicting them, which brought to the view delicate details and forms of each flower. As she explained later, she wanted to give the opportunity to every busy New Yorker to appreciate the uniqueness of flowers, and to share in her unique sensory experience of nature.

In her contribution to the exhibition catalogue for the show An American Place (1944), Georgia O’Keeffe elaborated further on her interest in flowers as a painterly subject, but also on different interpretations of her work, with which she mostly disagreed:

A flower is relatively small. Everyone has many associations with a flower - the idea of flowers. You put out your hand to touch the flower - lean forward to smell it - maybe touch it with your lips almost without thinking - or give it to someone to please them. Still - in a way - nobody sees a flower - really - it is so small - we haven't got time - and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time… So I said to myself - I'll paint what I see - what the flower is to me but I'll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it… Well - I made you take time to look at what I saw and when you took time to really notice my flower, you hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower - and I don't.

As Georgia O’Keeffe explained, flowers were ‘her flowers’, onto which others pinned their understandings that had nothing to do with her own.

An Unrelenting Fascination with Georgia O'Keeffe Flowers

Although intertwined in different theoretical readings, what definitely remains the truth is the remarkable beauty and aesthetic perfection of Georgia O’Keeffe flowers. Perhaps exactly because of these qualities, they do not cease to impress and to invite different interpretations. Although the artist died in 1986 at the age of 98, she remains an active participant in the global art market, with her works selling for astronomical amounts. Such is the case with the auction at Sotheby's in New York in 2014, where one of Georgia O'Keeffe flower paintings sold for $44.4 million, breaking a record for an artwork made by a female artist.

Although Will Gompertz, a BBC Arts Editor, may question the gender-bias at auctions when it comes to prices female artists fetch, and the decision by O’Keeffe’s Museum to sell this work, it is a significant step forward in establishing O’Keeffe as an important figure on the international art scene. It puts her, as Elizabeth Goldberg, Sotheby's head of American painting explains, in “the top tier of 20th Century artists on the market internationally, where it has always belonged”, and her flower paintings among the most recognizable images in both popular culture and art history.

Editors' Tip: Georgia O'Keeffe: Living Modern

This book explores how Georgia O’Keeffe lived her life steeped in modernism, bringing the same style she developed in her art to her dress, her homes, and her lifestyle. Richly illustrated with images of her art and views of the two homes she designed and furnished in New Mexico, the book also includes never before published photographs of O’Keeffe’s clothes. The author, Wanda M. Corn, has attributed some of the most exquisite of these garments to O’Keeffe, a skilled seamstress who understood fabric and design, and who has become an icon in today’s fashion world as much for her personal style as for her art. This fresh and carefully researched study brings O’Keeffe’s style to life, illuminating how this beloved American artist purposefully proclaimed her modernity in the way she dressed and posed for photographers, from Alfred Stieglitz to Bruce Weber.

Featured images: Georgia O'Keeffe - Black Iris, 1926 (detail). Captions, via Creative Commons; Georgia O'Keeffe - Red Canna, 1924 (detail). Captions, via Creative Commons ; Georgia O'Keeffe - Gray Line with Black, Blue and Yellow, 1923 (detail). Captions, via Creative Commons

Untitled (Skunk Cabbage), 1927

Over the course of her career, Georgia O’Keeffe depicted the skunk cabbage several times. This interest in serial imagery was partly informed by the ideas of one of her early teachers, Arthur Wesley Dow, who employed this method to highlight the importance of unique ways of seeing. Depicting the plant from above in Untitled (Skunk Cabbage) from 1927, she places the focus on the center of the plant, isolating it from its context. By leaving out the visual cues for the instant recognition, she highlights the plant’s distinctive shape and color. Emphasizing the plant’s patterned design of repeating curves and undulations, O’Keeffe explores the relationship between nature and abstract design. Ever since her nature-based abstractions had a debut on the New York art scene, the artist was often compared to the American modernist painter Arthur Dove. Often doing work in close dialogue with him, the artist here echoes Dove’s pastel in its treatment of both form and texture, as well as the artists’ shared belief in the rhythms and dynamism inherent to the natural world.

Featured image: Georgia O’Keeffe - Untitled (Skunk Cabbage), 1927, via yama-bato.tumblr.com

Jimson Weed - White Flower No. 1, 1932

A remarkably bold and elegant representation of the artist’s mature intent and aesthetic, the painting Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1 from 1932 shows the plant as monumental, filling the picture plane nearly to entirety. She has employed this plant as a subject on multiple occasions from a variety of viewpoints. The beauty of this poisonous plant has first attracted the artist when she found a bunch of them near her home in New Mexico, describing it as “a beautiful white trumpet flower with strong veins that hold the flower open and grow longer than the round part of the flower – twisting as they grow off beyond it”. Since the weeds bloom when the sun sets, the artist explained she could almost feel “the coolness and sweetness of the evening”. In her depiction, she has managed to transform the poisonous into sublime, presenting what she taught was actually the essence of the plant.

Featured image: Georgia O’Keeffe - Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1, 1932. Captions, via Creative Commons

My Autumn, 1929

Carefully balancing realism and abstraction, the painting My Autumn from 1929 is a remarkable synthesis of form and color. Intricately layering objective and subjective meaning, this painting is characteristic of her work of the period with its simplified abstraction and vibrant color. Much of the artist’s inspiration in this period came from Lake George, where she has been spending time with her husband, Alfred Stieglitz. While O’Keeffe painted all year around, she felt that the autumn was her time for painting. With its vibrant hues of yellow and crimson, this painting completely embodies her personal emotions and passion towards the season. Using balanced values of darks and lights, the artist here explores color, form and light - something she has always perceived as the basis of the painting. Combining nature with abstraction, she has layered various visual interpretations into an almost flattening design.

Featured image: Georgia O’Keeffe - My Autumn, 1929, via pictify.saatchigallery.com

Black Iris, 1926

The painting Black Iris from 1926 shows the magnified blossom removed from its natural context, manifesting the highly evocative and sensual overtones that are the hallmarks of O’Keeffe’s finest flower paintings. Combining the artist’s personal association with her botanical subject, the composition of the painting is at the same time rapturous, feminine and deeply modern. Despite being explicitly feminine, the work is convincingly powerful. Ascribing personal association to the flower that went beyond their design possibilities, her composition is highly intimate, evoking the mystical and spiritual qualities of her best works and their powerful visual impact. The sensuality and near eroticism are implicit, arousing a great hubbub among the public and the critics. Due to the spectacular size, outrageous color and scandalous shapes, this painting, along with the similar others, fueled the public’s interest in the woman who was at the same time exposed and mysterious.

Featured image: Georgia O’Keeffe - Black Iris, 1926. Captions, via Creative Commons

Gray Line with Black, Blue and Yellow, 1923

Regarded as one of the masterpieces of her career, the painting Gray Line with Black, Blue and Yellow from 1923 combines precisely delineated, undulating folds and lucid three-dimensional forms in a way that suggests both a portrayal of the plant and the female anatomy. This tension and potent ambiguity are further enhanced by the cropping of the frame, a compositional device often used in photography of the time, especially in Alfred Stieglitz works. With its richly nuanced blend of colors, the painting evokes Dow’s mantra of “filling space in a beautiful way”. The key strength of this painting resides in its derivation from natural, organic forms.

Featured image: Georgia O’Keeffe - Gray Line with Black, Blue and Yellow, 1923. Captions, via Creative Commons

Jack in the Pulpit IV, 1930

The painting Jack in the Pulpit IV from 1930 is part of a series of six canvases where the artist has depicted this common North American herbaceous flowering plant at Lake George in New York. Beginning with the striped and hooded bloom rendered with a botanist’s eye, these Georgia O’Keeffe flower paintings subsequently evolved towards the abstraction, ending with the essence of the flower, a black pistil painted against a black, purple and gray background. This canvas represents a midpoint in the process. Presenting a magnified view of the spadix set against the spathe’s cavernous, dark purple interior, the composition is bifurcated by a narrow strip of white. Believing that the immanence of nature could be discovered in and through the refinement of form, she uses abstraction as an equivalent for knowledge. The most profound knowledge of the subject, embodied in its closest view, reveals its abstract form.

Featured image: Georgia O’Keeffe - Jack in the Pulpit IV, 1930. Captions, via Creative Commons

Hibiscus with Plumeria, 1939

Following the fame that surrounded her flower paintings, Georgia O’Keeffe was invited by Dole Pineapple Company to Hawaii in 1939 to create paintings for the island's advertising campaign. After visiting Maui, Oahu, Hawaii, and Kauai, she created around twenty canvases of the rich nature of the archipelago depicting dramatic gorges, waterfalls, and tropical flowers. A part of this series, the painting Hibiscus with Plumeria shows pink and yellow petals towering against a clear blue sky, transforming the delicate blossoms into monumentality. As opposed to her other flower pieces where the artist has used around fifty colors in multiple shades, this painting has at most five colors used – the blue, white, yellow, orangey-brown, pink and dark blush. Flowers are rendered in a rather simple way, just detailed enough that they can be identified.

Featured image: Georgia O’Keeffe - Hibiscus with Plumeria, 1939. Captions, via Creative Commons

Red Canna, 1924

Georgia O’Keeffe has produced a number of paintings of the canna lily plant, primarily abstractions of close-up images. The painting Red Canna from 1924 is part of this series. The artist explained that she wanted to reflect the way she saw these flowers, expressing herself through the use of vibrant colors like red, yellow and orange. Similarly to many other flower paintings, this work has been called erotic for its suggestion of the female genitalia. The American journalist Paul Rosenfeld, who owned one of her Red Canna paintings said:

...there is no stroke laid by her brush, whatever it is she may paint, that is not curiously, arrestingly female in quality. The essence of very womanhood permeates her pictures.

A close-up of the flower with streaks of light blue and gray, this painting completely immerses the viewer in the blossom, conveying the way the artist has experienced it.

Featured image: Georgia O’Keeffe - Red Canna, 1924. Captions, via Creative Commons

Calla Lilies, 1924

Following her first depiction of the calla lily in 1923, O’Keeffe created a series of eight compositions in both oil and pastel. One of two paintings of the subject in 1924, Calla Lilies show three blooms in a single composition. Regarded as one of the most sophisticated and modern of her explorations of the subject, it shows the ideal combination of the organic subject and formalist design. A sophisticated meditation on color, form and line, the provocative composition is the genesis of her interest in the blossom. Having a certain cool detachment to the plant, she focused on its physical attributes, capturing the flower at various angles and settings. White flowers are punctuated by their yellow stamen and set against a background of similar whites and grays in order to blur the distinction between the flower and the background.

Featured image: Georgia O’Keeffe - Calla Lilies, 1924, via sothebys.com

Red Poppy, 1927

As another of her series, Georgia O’Keeffe has produced the total of seven paintings of poppies. The most famous ones are The Red Poppy from 1927 and Oriental Poppies from 1928. A perfect example of her close-ups that fill the entire canvas, Red Poppy is marked with vibrant red and orange tones that pull the viewer directly into the artwork. Peering into the bright orange petals, the artist reveals the velvety dark interior, creating a drama by the juxtaposition of vivid color and intrusive close-up. The absence of context in the painting presents the flower in a new light as a pure abstract. This stunning Georgia O’Keeffe flower painting was declared a groundbreaking art masterpiece, and in 1992, the US post office decided to pay tribute to it by making a series of stamps based on this very painting.

Written by Eli Anapur and Elena Martinique.

Featured image: Georgia O’Keeffe - Red Poppy, 1927. Captions, via Creative Commons

Can We Help?

Have a question or a technical issue? Want to learn more about our services to art dealers? Let us know and you'll hear from us within the next 24 hours.